While building a baseball game, whether tabletop using cards and dice or video game, the most satisfying aspect is when you finally develop those magical formulas and mathematical equations that are going to allow you to derive ratings or create cards. It’s that aha moment. You’ve spent countless hours researching and many sleepless nights pondering your game mechanics, only to finally land on something you feel is absolutely brilliant.

Then, the chaos sets in.

In life, and in baseball, we like round numbers. We want everything to add up to 100%. We want everything to conclude in a tidy manner, and we hope nothing will stand in the way of that goal.

When you analyze baseball statistics, and the ball players that generate them, it stands within reason to expect a baseball player with only a handful of at bats or innings to potentially break the game mechanics. For example, if a batter hit three home runs in just four at-bats during a season, it would be nearly impossible to create game mechanics to accommodate this.

In Strat-o-Matic for example, even if every dice roll on the batter’s card resulted in a home run, it still would be impossible to recreate this statistical accuracy. But we’d be okay with that. After all this is an aberrant outcome; a small data pool.

We would be okay with this player not being able to produce home runs in 75% of his at bats.

But what happens when a ball player that has 600 or 700 plate appearances under his belt manages to absolutely destroy your game mechanics? It’s possible. And it happens. It happens with the best of the best. Let me explain.

In working on my game, High Leverage Baseball, I first took a look at each of the individual outcomes. I decided I was going to compare the likely percentage outcome of each, and assumed it would be far less than 100% even if you looked at the best seasons ever.

- Singles

- Infield Singles

- Doubles

- Triples

- Home Runs

- Walks

- Strikeouts

- Hit By Pitch

I decided I was going to rate each batter and pitcher in these areas. The batters would have a rating between 1 and 100; 100 being the best ever. Bonds with 73 home runs. Suzuki with 225 singles. Earl Webb with 67 doubles. Mark Reynolds with 211 strikeouts in a smaller-than-expected plate appearance pool.

My assumption was that when you compared these ‘maxes’—the best of the best—the total percentage would not exceed 100. This means that if the best ever had a double in 10% of their plate appearances, and a triple in 5%, and a home run in 9%, and a strikeout in 33%, that when you added up all these legendary numbers it would not exceed 100%.

Boy, was I wrong.

I thought by creating a rating from 1 to 100 based on the best ever, I would have a pretty unique and fun game mechanic. It sounded very, very simple on paper, but as I’m about to show you the best ever destroyed this dream.

Eventually I had to go to plan B. It’s not within the scope of this article to discuss how I adjusted the mechanics, but I do want to show you how the best of the best are easily able to break a seemingly fundamentally strong game mechanic.

So, let’s look at each of the above categories compared to plate appearances. We will reduce intentional walks from plate appearances, as those are a manager’s decision and not worked for, so to speak.

Infield Singles – Ichiro Suzuki, 2009 season, 63 infield hits in 663 true plate appearances… 9.50%

In the 2009 season Ichiro Suzuki had 63 infield hits. An absolutely ridiculous number. If you compare this to 663 true plate appearances, meaning plate appearances minus intentional walks, approximately 9.5% of the time that he stood inside of the batter’s box resulted in an infield hit. Nearly 1 in 10 plate appearances. Let that sink in.

Non-Infield Singles – Ichiro Suzuki, 2004 season, 168 non-infield singles in 743 true plate appearances… 22.61%

In the 2004 season Ichiro Suzuki had another statistically ridiculous year, managing to produce 168 non-infield singles in a complete season. Forget the fact that he also produced 57 infield hits that year. Suzuki managed more non-infield singles – 168 – then the number of games played in a baseball season.

Doubles – Earl Webb, 1931 season, 67 doubles in 652 true plate appearances… 10.3%

Awarded the MVP in the 1931 season, Boston slugger Earl Webb managed to crush 67 doubles in a complete season. Basically, Earl managed to reach second base in over 10% of his plate appearances.

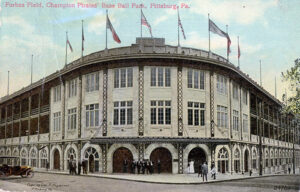

Triples – Owen/Chief Wilson, 1912 season, 36 triples in 643 plate appearances… 5.60%

This might be one of the most ridiculous statistics you will ever look at in the history of baseball. A towering home run blast is one thing, but for your batted balls to find the perfect gap over and over again to produce 36 triples in a year is absolutely ridiculous. The 1912 Pirates played at Forbes field which was about 457 feet to the deepest part of the ballpark, and slightly over 400 to the gaps. It goes without saying that Chief Wilson had mastered the art of playing his field. But beyond that, considering half of his games were away from home…

Home Runs – Barry Bonds, 2001 season, 73 home runs in 629 true plate appearances… 11.61%

The 2001 season felt like we were truly living in the future; not just from a technological standpoint, but also in Major League Baseball. Barry Bonds blasted a bloated 73 home runs; a dinger in over 11.5% percent of his plate appearances. In that season Barry managed to make us forget about the chaos that came nearly one year before with the Y2K fear, and serve up a statistic our brains could simply not process.

Hit By Pitch – Ron Hunt, 1971 season, hit by a pitch 50 times in 637 true plate appearances… 7.85%

I don’t know what is more impressive, and maybe you can help me decide – being hit by 50 pitches in a complete season, or managing to be hit by 50 pitches and not land on the injured reserve list for an extended period of time. In 1971, Montreal’s Ron hunt was pelted by pitches 50 total times. This allowed him to push his on-base percentage to 0.402 for the season.

Walks – Barry Bonds, 2002 season, 130 walks in 544 true plate appearances… 23.90%

Now, understand that Babe Ruth had some impressive walk statistics, but back in his era intentional walks weren’t tracked. In 1923 the Babe had 170 total walks, but it had been estimated that 80 of these were intentional. Intentional walks weren’t tracked until the 1955 season. For this reason we have to look at batters that competed after this year.

In 2002, the year after Barry Bonds crushed 73 ding dongs, he reached 130 natural walks. This excludes the 68 intentional walks that occurred during that season. It goes without saying that pitchers were pitching around him. His home run total dipped below 50 that year, but his on base percentage landed just a hair below 0.500.

Strikeouts – Mark Reynolds, 2010 season, 211 strikeouts in 589 true plate appearances… 35.82%

No batter was arguably more prolific at whiffing than Mark Reynolds. He had multiple seasons of over 200 strikeouts, doing so nearly a decade before strikeouts in baseball peaked.

Adding Up the Damage

Now it’s time to add up the damage. Based on pure statistics, if we wanted to assign a 100 rating in our game based on the best ever in each category, and rate the other players in a relative sense, here would be the top percentages of each outcome relative to true plate appearances:

- Singles – 22.61%

- Infield Singles – 9.50%

- Doubles – 10.3%

- Triples – 5.60%

- Home Runs – 11.61%

- Walks – 23.90%

- Strikeouts – 35.82%

- Hit By Pitch – 7.85%

Now let’s imagine you are the ultimate super player with a 100 rating in each category. The total of these percentages if you were that player add up to 127.19%. You can see the best of the best have just broken your game mechanic.

While you will never have a player with 100 ratings in each category, simply allowing for that possibility pushes the math above 100% and breaks the rating system. For this reason, all the sweat, brain power, and mathematical juggling that you’ve just done in the last two months has just been burned down in flames.

In this case, the mechanics for my baseball game were destroyed. You can’t have this many possible outcomes.

I was forced to retreat with my tail between my legs, angry but not angry at these amazing seasonal statistics. I both stood in awe and wept in the corner. But as we must do, I rose from the ashes, and found another way to make this happen.

I’m not going to get into the mechanics of my tabletop baseball game. That’s certainly not the point of this article. What I hoped to achieve by presenting these numbers to you is to show you that not only is baseball filled with truly amazing statistical anomalies around every corner, but they can force you into some funkadelic mathematical situations that don’t add up to a tidy 100%.

Addendum

I wanted to end with a little bit of more specific information on why my game mechanics were broken by the record breakers, and how record breakers make it challenging when building game mechanics to replicate the records. Not in all cases obviously, but you need to be savvy and expect the train coming down the tracks.

The issue lies in the fundamental nature of probability and how it governs game mechanics. In a system where each outcome—singles, doubles, triples, home runs, walks, strikeouts, infield singles, and hit by pitch—is assigned a percentage likelihood, those probabilities must sum to no more than 100%. This is because every plate appearance can only result in one of these outcomes, and the total probability space cannot exceed 100%.

When you attempt to assign percentages based on the best-ever statistical outcomes in baseball, as shown above, the combined total of those probabilities exceeds 100%. For example, with singles at 22.61%, infield singles at 9.50%, doubles at 10.3%, triples at 5.6%, home runs at 11.61%, walks at 23.9%, strikeouts at 35.82%, and hit by pitch at 7.85%, the total comes to 127.19%. This creates an impossible system because it implies that in 127.19% of plate appearances, something will happen—an absurdity since only 100% is possible.

This forces a compromise in the mechanics. To make the system work, you must scale these percentages down so that they fit within the 100% limit. However, this scaling has a significant consequence: it reduces the likelihood of any single outcome occurring to the point where even record-setting performances cannot be faithfully replicated.

For instance, if Barry Bonds’ 2001 home run percentage of 11.61% must be scaled down to fit alongside all other outcomes, the chances of hitting a home run in the game will be reduced below his historical level. Similarly, Ichiro Suzuki’s 2004 rate of 22.61% for singles would have to be diminished, meaning his unparalleled ability to get base hits can no longer be fully represented.

This is where the mechanics break. By attempting to include all outcomes at their record-setting levels, the system violates the fundamental constraint of probability, rendering it unplayable. To fix this, you have to shrink each percentage, but doing so sacrifices the authenticity of the mechanics. The compromise means no individual outcome can ever achieve its historical high, undermining the ability to reflect the true brilliance of baseball’s greatest performances.

In short, the very thing that makes baseball extraordinary—the ability for players to set seemingly impossible records—also makes it extraordinarily difficult to create a game mechanic that both honors those feats and fits within a playable framework. Balancing realism with mathematical constraints becomes the central challenge.

Retired editor and small business owner; baseball fanatic. My love for statistics in math was launched in my early teens while compiling and analyzing statistics from Strat-o-Matic baseball. Currently working on my first game - High Leverage Baseball - as part of a startup gaming company called Massive Tension Gaming.

- Steve Shawhttps://sabrbaseballgaming.com/author/bhud/

- Steve Shawhttps://sabrbaseballgaming.com/author/bhud/

Also if you had created the rating scale in the year 2000, then Bonds would’ve broken the scale in 2001, Ichiro in 2004 and again and 2009, then Reynolds in 2010. Four times in the span of 10 years you would need to recompute the game’s ratings.

I think the problem is you are first dividing each category by plate appearances before adding them together. It might make more sense to add the raw totals together first and derive plate appearances from them. So hits = 63 (Ichiro) + 168 (Ichiro) + 67 (Webb) + 36 (Wilson) + 73 (Bonds) = 407. Walks + HBP = 130 + 50 = 180. Strikeouts = 211. You should probably add non-strikeout outs as well (this might be Woody Jensen in 1936 with 480 AB – H – SO). So plate appearances = 407 hits + 180 BB/HP + 211 SO + 480 non-K outs = 1,278. If you don’t want to add non-K outs you’re still at 798 PAs.

So then each category would be divided by 1,278 plate appearances, and the percentages for the super player who led in every category would add to 100%.

That’s a very good point. Record breakers will continue to break the mechanics, unless we take that possible expansion into consideration.